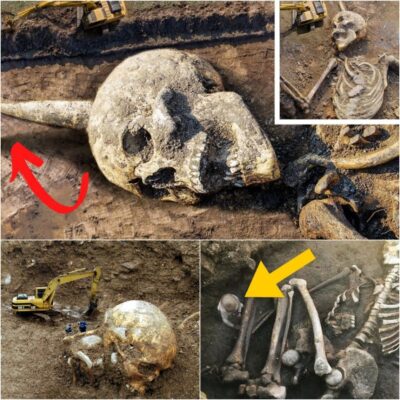

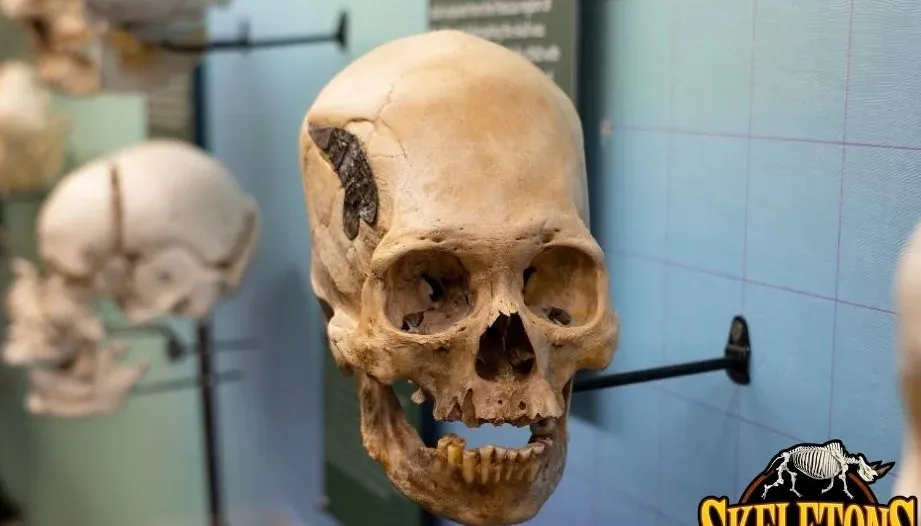

The Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma has unveiled an intriguing archaeological discovery: a 2,000-year-old Peruvian warrior’s skull fused with metal, providing one of the world’s earliest examples of advanced surgery. Believed to belong to a man injured in battle, the skull underwent pioneering surgical intervention, where a piece of metal was implanted to mend the fracture.

According to experts cited by the Daily Star, the successful outcome of the surgery makes this ancient Peruvian skull a crucial piece of evidence, highlighting the advanced surgical capabilities of ancient civilizations. The specific skull in question represents a Peruvian elongated skull, showcasing a form of ancient body modification. In this practice, tribe members intentionally deformed the skulls of young children, employing methods such as binding with cloth or pressing the head between two pieces of wood for extended periods.

The Museum stated, ‘This is a Peruvian elongated skull with metal surgically implanted after returning from battle, estimated to be from about 2000 years ago. One of our more interesting and oldest pieces in the collection. We don’t have a ton of background on this piece, but we do know he survived the procedure.’ The tightly fused broken bone surrounding the repair attests to the success of the surgery.

Originally part of the museum’s private collection, the skull garnered increased public interest, leading to its official display in 2020. The artifact’s origin in Peru is noteworthy, as the region has a historical association with skilled surgeons who devised intricate procedures for treating skull fractures, a common injury during the use of projectiles like slingshots in ancient battles.

Elongated skulls were prevalent in ancient Peru, achieved by applying force to a person’s cranium, often through binding it between two pieces of wood. Various explanations exist for skull elongation, ranging from societal elites marking themselves out to serving as a form of defense. Subsequent archaeological findings revealed that Peruvian women with elongated skulls were less prone to serious head injuries compared to those without.