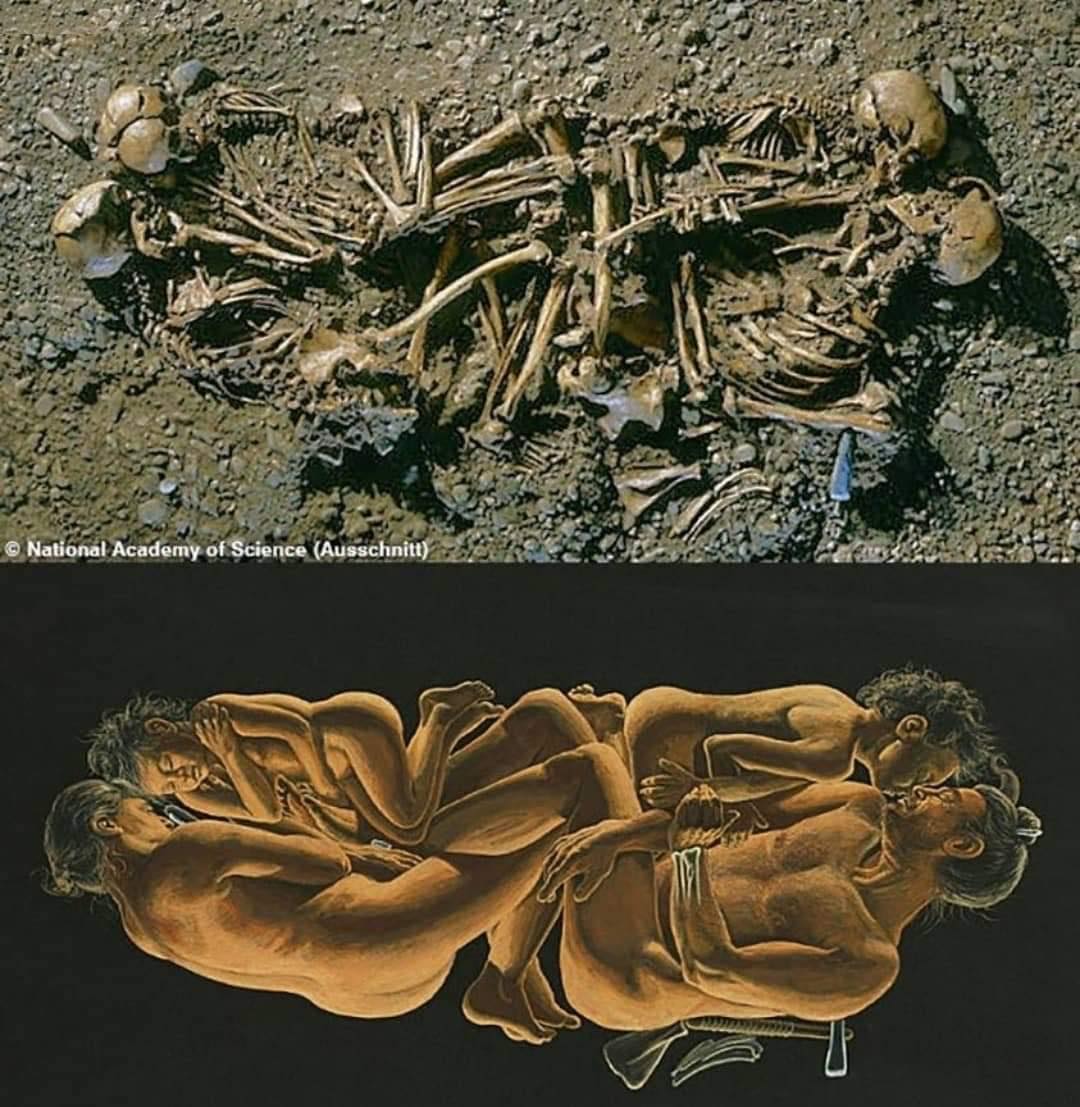

The find consists of two parents and two sons who were buried together after being killed in a violent conflict over some of the most fertile farming land in Europe.

The archaeologists who examined the bones said the burial provides evidence of a shift in social organisation from communal living to societies with large social differences between people.

“It provides evidence that will allow us to understand the rise of societies that are more modern,” said Dr Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at Bristol University who was a member of the team.

The site was discovered four years ago during quarrying at Eulau in Saxony-Anhalt, about 120 miles south-west of Berlin. Along with some individual burials there are four group burials in which more than one individual was interred at the same time.

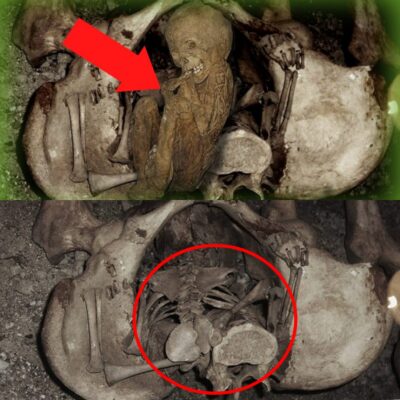

The group burials, which appear to have happened together, tell a story of violent deaths. One skeleton has an arrow tip lodged in one of its vertebrae. Several of the skeletons have fractures that have not healed, showing that they must have happened shortly before death. Pike said they were probably trying to hold on to land in the face of raids.

“This particular area is considered to be one of the most fertile areas of Europe. So if people are looking for areas to settle they will be looking for these kind of soils, which might have contributed to some of the interpersonal violence,” he added.

The people were members of the Corded Ware culture, named after their practice of decorating pots using twisted cord. By analysing bone samples, the scientists have shown that the arrangement of the bodies reflected family groups. Children who were related to the adults in the same grave were buried facing them; unrelated children were buried behind the adults.

“Whoever buried them knew … it was very important that you signify genetic relationships in the way that you lay the [bodies] out,” said Pike. The finds are documented in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Burial as a nuclear family is different from the custom earlier in the neolithic era. Typically, archaeologists find mass graves of hundreds of individuals with little to distinguish them.

The team also examined evidence of where the people had grown up by analysing the combination of different forms of strontium in their teeth. The ratio of strontium isotopes depends on a person’s diet during childhood and reflects the dominant rock types in the area. While the men and children had a strontium profile that indicates they were raised nearby, the women came from outside the area.

Pike said this was evidence of a patrilocal society, where families “married out” their daughters, either to avoid inbreeding or build allegiances with neighbours.